Paradise Glitch : Simon Bejer

General Assembly is pleased to present Paradise Glitch, a solo exhibition of new works by Simon Bejer. Exuberant imagery and a vibrant palette define these works where the natural world collides with the realms of urban landscape, kitsch, art history, and entertainment culture.

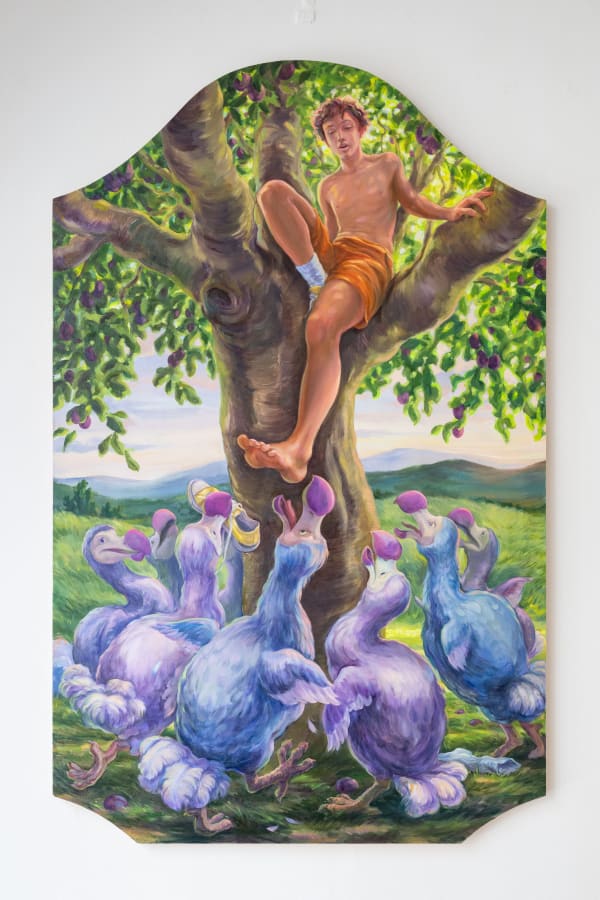

The dodo, the flightless bird that had become extinct by 1662 due to invasive predators and overhunting, is a reoccurring motif. The doomed bird fascinates Bejer, who delights in its unlikely story of evolution, demise and subsequent rise to mythical status through art and culture. For Bejer, conjuring new narratives and contexts for the dodo does not cure its extinction, but can resurrect what has been lost in imaginative and provocative ways. In the monumental diptych The Orpheus Conundrum, a fantastical harmony characterises the commingling of diverse species, tamed by a young human and his flute. The painting’s implausible assembly of figures echoes the seventeenth-century works of Jan Bruegel or Roelant Savery, whose depictions of Eden conjure wondrous worlds, and celebrate the sheer joy of painting and artistic imagination. As the mythical figure of Orpheus musically enchanted his animals, so Bejer hopes to beguile his viewers with an almost hallucinatory abundance verging on kitsch. The work may also serve as an allegory, questioning the ability of art to tap into a divine harmony, to cast an enchanting spell, and to construct a myth.

For many of the paintings in Paradise Glitch, Bejer has used shaped supports referencing the ornateness of Baroque and Rococo altarpieces. He subverts the religious or hierarchical implications of such forms with scenes that are quotidian, absurd, humorous, unsettling and even sinister. Melancholy, longing, and decay are suggested in the paintings Flyover and La Campagna with its florid frame, found and embellished by the artist. Whether these paintings glorify or lament the banal landscapes of highway overpasses and crumbling concrete roads remains for the viewer to decide. Nowhere is that ambiguity more present than in Big Game, where an intimate scene of instruction leaves viewers pondering the relationship between a tender moment and its implications for society.

In the installation Egg Poacher, which repurposes a vintage arcade claw machine, Bejer invites the audience to participate in his world. The installation’s vitrine-like centre, brimming with plants and a group of outsized pink eggs in a nest, stages a contained fragment of a precious paradise. The menacing claw, an extension of the player’s arm, threatens to disturb this jungle idyll. Stickered slogans on the machine’s glass exterior

both entice and admonish the audience while painted scenes of pursuit and capture reiterate the stakes. The theatricality and artifice present in this work are influenced by Bejer’s extensive background in stage design; the qualities of performance, illusion, and narrative strongly informing his practice.

The ceramic fragments that constitute Colossus were once part of a sculpture that Bejer had executed but which was severely damaged in the kiln during firing. After the incident, he decided to reassemble, gild and display the remnants. Bejer’s use of scientific laboratory stands emphasises the inherent fragility of the fragments, while calling to mind the museological preservation of relics and the ultimately experimental and often volatile nature of the creative practice. In harkening to the legendary Colossus of Rhodes, which presided over its island’s port until an earthquake caused it to collapse in around 230 BCE, Bejer’s diminutive Colossus makes history and mythologising part of the work’s interpretative fabric. Here, too, resides a link with the dodo motif — the role of art in de-constructing and re-constructing historic narratives, outright fallacies, and magically resuscitating what has been apparently lost for good.